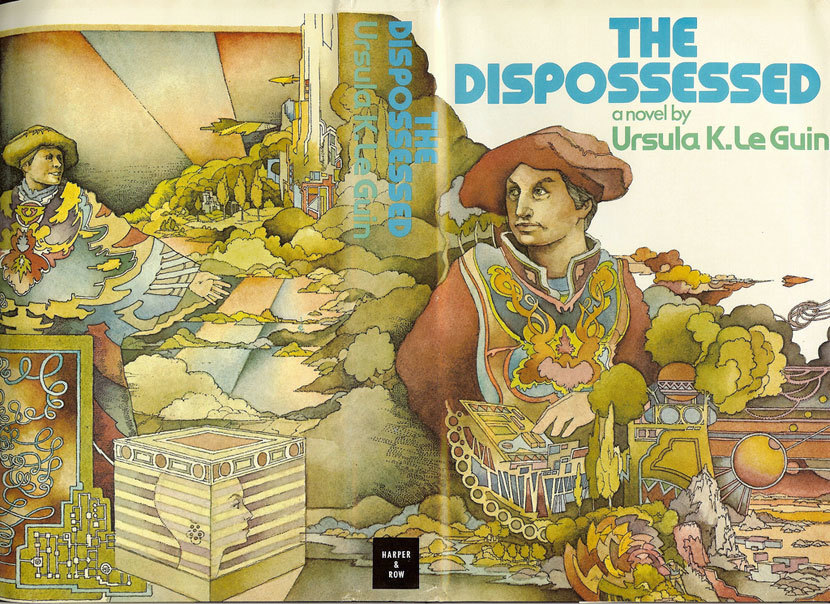

Fred Winkowski’s jacket design for the first American edition of The Dispossessed (Harper & Row, 1974).

“It is our suffering that brings us together,” Ursula K. Le Guin wrote. “It is not love. Love does not obey the mind, and turns to hate when forced.” Almost 40 years before playwright Young Jean Lee comforted us with stories and songs of isolation and pain, Le Guin explored why suffering was the thread that stitched our lives together.

“The bond that binds us is beyond choice,” Le Guin (1929-2018) wrote in her 1974 science fiction novel “The Dispossessed.” “We are brothers. We are brothers in what we share. In pain, which each of us must suffer alone, in hunger, in poverty, in hope, we know our brotherhood.”

United in their effort to endure hardship, and encouraged to place community need above individual, the anarchist people of Anarres eke out an existence. But things on Anarres are unraveling; people are beginning to act like capitalists. When the physicist Shevek visits his neighboring planet, Urras, where its capitalist, patriarchal system also happens to be under attack, he gets caught up in its revolution. Speaking through Shevek, Le Guin wrote:

“We know that there is no help for us but from one another, that no hand will save us if we do not reach out our hand. And the hand that you reach out is empty, as mine is. You have nothing. You possess nothing. You own nothing. You are free. All you have is what you are, and what you give.”

Why are these important–the flash of an album crush, the steady burn for a favorite book? Because they both speak to our fractured, distracted selves and society. Because their answer–reverberating across the decades–is to deepen and widen connection so that we might find what has been lost: shared purpose and agency that provide value to our lives and our communities.

Thirty-seven years after the publication of “The Dispossessed,” the struggle for connection in a rich and isolated society became the focus of Lee’s 2011 script “We’re Gonna Die, a series of monologues interrupted by song. In one heartbreaking story, read by Adam Horovitz of the Beastie Boys, a young nephew who has jokingly hidden himself in his uncle’s room, witnesses his uncle’s self-loathing and pain. It is this story about weird Uncle John, whose loneliness must be hidden from his family, which most clearly echoes Le Guin’s novel.

As Shevek’s stay on Urras lengthens, he begins to understand the deep costs demanded from the people for their wealth. He sees the weakness and strength in his home planet and its anarchist system, and grapples with the inherent tension between individual and community. Here is Le Guin’s Shevek, one last time:

“Anarres is all dusty and dry hills. All meager, all dry. And the people aren’t beautiful. They have big hands and feet, like me and the waiter there. But no big bellies. They get very dirty, and take baths together, nobody here does that. The towns are very small and dull, they are dreary. No palaces. Life is dull, and hard work. You can’t always have what you want, or even what you need, because there isn’t enough. You Urasti have enough. Enough air, enough rain, grass, oceans, food, music, buildings, factories, machines, books, clothes, history. You are rich, you own. We are poor, we lack. You have, we do not have. Everything is beautiful here. Only not the faces. On Anarres nothing is beautiful, nothing but the faces. The other faces, the men and women. We have nothing but that, nothing but each other. Here you see the jewels, there you see the eyes. And in the eyes you see the splendor, the splendor of the human spirit. Because our men and women are free–possessing nothing, they are free. And you the possessors are possessed. You are all in jail. Each alone, solitary, with a heap of what he owns. You live in a prison, die in a prison. It is all I see in your eyes–the wall, the wall!”

- “The Dispossessed” by Ursula K. Le Guin (public library).

- “Uncle John” read by Adam Horovitz from the album “We’re Gonna Die†script (public library) by Young Jean Lee and her band, Future Wife.

- Miserable, but never alone.

Leave a Reply