“A natural place of solitude gives us the opportunity to see and value our place in this world and … patience to wait for the unexpected.â€

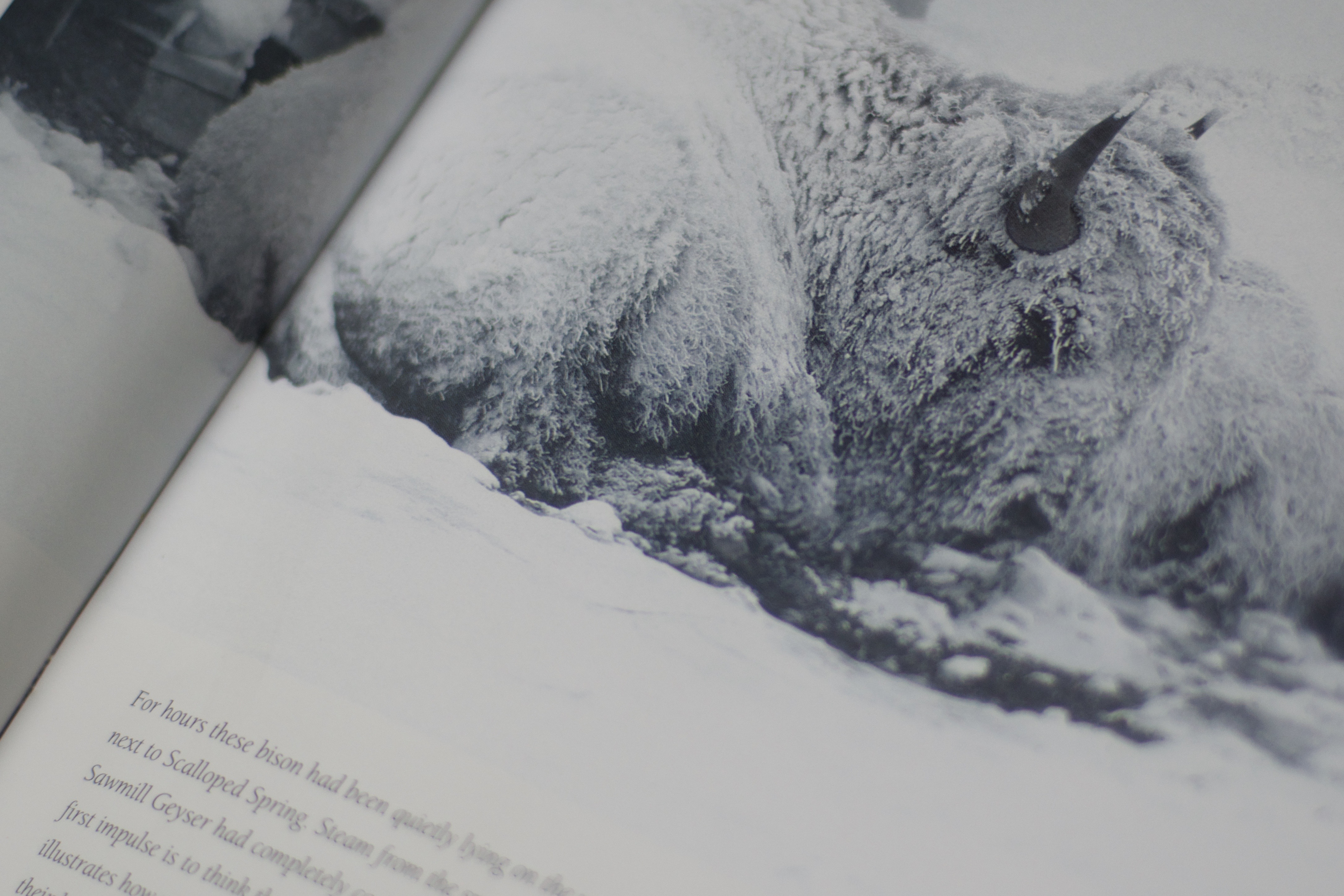

A bison near a warm stream from “Silence and Solitude: Yellowstone’s Winter Wilderness” by Tom Murphy.

Written across fresh snow, a line of mouse track collided with an imprint of hawk feather to record a moment when winter stripped nature and story to their basic elements, survival and death. Yet even in this minimalist environment is beautiful abundance that is illustrated in “Silence and Solitude: Yellowstone’s Winter Wilderness” by Tom Murphy.

The exquisite excess in the act of survival captivates the imagination of Murphy, a naturalist, photographer and author who has spent more than four decades recording the harsh beauty and tenacious spirit of Yellowstone National Park, one of the few remaining wild places in the United States.

In the volcanic landscape of snow and steam, of hot springs and freezing creeks, change is marked in geological time, seasonal shifts and in the split second. For Murphy it is a land that nurtures life, freedom and beauty, especially in winter when Yellowstone is a silent place filled with strength, power, endurance, patience, waiting, and expectation, according to “Silence and Solitude” (2002), which embodies these same meditative qualities:

“Snow could be just a dull state of water. Instead, snow forms wild and graceful drifts, some with sharp, hard edges next to sensuous, soft curves. Some snow ripples and swirls, twisting along among grass, sagebrush, and rocks. Where there is no wind, snowstorms form humps on the rocks, logs, branches, and grass clumps. … It maintains an infinite variability that invites me to keep watching.”

Snow reveals, creates definition, and shifts perspective to isolate what would normally go unnoticed. It records moments like this conflict between hawk and mouse that Murphy noticed as he skied across Yellowstone’s Lamar Valley one January afternoon:

“A mouse had been traveling in the fluffy new crystals on top of the old snow, apparently feeding on exposed grass seed stalks. There were several nice photographs of tracks and grass stems, so I spent quite a bit of time following these tracks for maybe an eighth of a mile. I was surprised to find this end. A hawk had seen the mouse; the mouse had seen the hawk. The mouse made a hard left and then made six jumps — and was food for the hawk. The light at this time was very poor, so I went on skiing for a few hours, watching the light. Just before sunset, I skied back and was lucky; the light provided some contrast to see the tracks better and the wind had not come up and blown them away.”

Murphy’s curiosity and gratitude for nature are exposed and expressed in his photographs and writing, which has appeared in National Geographic, Newsweek, Audubon and the Corporation for Public Broadcasting. His dedication is evident in the 80 to 100 days he spends within the national park’s borders each year, and the five photography books published.

Art and science both originate from a need to understand the world we live in, said Murphy, who draws on both when he photographs Yellowstone in winter, a place of rare beauty and near impossible discoveries now imperiled by climate change.Â

Anticipated climate change to the Yellowstone ecosystem. The NASA Earth Observatory map by Joshua Stevens.

In “Silence and Solitude,†Murphy writes:

“The solitude you can find in Yellowstone promotes an independence of spirit. These experiences refresh our lives, teach us self-reliance, and reveal the wisdom of the cycles of the land. By contrast, the noises and distractions of our modern world induce loneliness and isolation. A natural place of solitude gives us the opportunity to see and value our place in this world and gives us the necessary patience to wait for the unexpected.â€

Reorienting ourselves in place and import within the larger needs of the world was an underlying argument of Thomas Berry (1914 – 2009), a pioneer in the field of religion and ecology who argued that we could not rescue ourselves from ecological crisis without tending to the Earth.

Yellowstone, our oldest national park, has long served to reconnect humans with nature. In 1883, The New York Times described this land of fire and ice as an “almost mystical wonderland.†More than a century later, that reverence appears in Murphy’s photographs.

It is in the photograph of a thin elk, its head submerged in a stream as it chews on waterlogged reeds. It is found in the three bison crusted with ice, their frozen coats illustrating how well the hair insulates them. And it exists in the picture of mountainside scorched and scarred by 1988 wildfires that killed millions of pine trees. Murphy writes:

“A stand of dead trees has a beauty much like an animal’s skeleton. The graceful stark bones of a rib cage or articulated vertebrae are beautiful like this group of dead lodgepole pine. The smooth arcs of the trees’ shadows create a nice counterpoint to the hard vertical lines of the forest’s skeleton.”

Murphy developed an intimacy with wide-open places during his childhood on a cattle ranch in western South Dakota. There he developed a deep love for spacious land, as well as a determination to not spend his lifetime chasing cows, according to his website autobiography. After earning a degree in anthropology, he spent many years combining photography with anthropological fieldwork.

He first went alone into the park in 1985, according to his longtime friend, travel writer and a founding editor of Outside magazine Tom Cahill, who questioned Murphy’s wisdom when he skied into the backcountry with simple cameras, 20-year-old outdoor gear, and thin red dress socks in old leather boots. Two weeks and 125 miles later Murphy skied out, right on schedule, Cahill recalled. Murphy had lost 10 percent of his body weight and survived one of the worst winter storms of the decade, his friend wrote in the wrote in the 2002 forward to “Silence and Solitude.”

Cahill might think his friend foolhardy to brave the elements in 50-cent socks, but he expressed only admiration for Murphy’s ability to tell a story with an image.

“This is because Tom, who has been a guide in the park for two decades, knows the flora and fauna and the natural rhythms of the place in the way that he knows the beating of his own heart,” Cahill wrote in “Silence and Solitude.” “Consequently, his photographs are not simply stunning or striking: they are also knowledgeable and even wise.”

The snow that draws Murphy to Yellowstone is critical to the park’s ecosystem, but less of it is falling and it no longer accumulates the way it used to, according to The New York Times, which in November reported on climate change’s threat to Yellowstone with extensive reporting, photography and time-lapse video. By mid-century, scientists predict that some areas in the park will see a sharp decline in snowpack, which worries ecologists like Michael Tercek who has worked in Yellowstone for 28 years and told the newspaper that, “by the time my daughter is an old woman, the climate will be as different for her as the last ice age seems to us.â€

While Tercek and other scientists track snowpack inconsistencies, Murphy records it with film winter after winter. One constant, though, has been the photographer’s frugality and whittled-down approach to the two biggest challenges of winter work — extremes in temperature and light. He still uses a 35-millimeter camera, a handful of lenses, and the same thin red socks, according to “Silence and Solitude.”

In a place where temperatures can dip 50-degrees below freezing, Murphy wrote that he continues to use tripods 99 percent of the time, although they are cold, pinch his fingers, and are heavy and awkward on his skinny shoulders. When traveling through steam in thermal areas, he learned to keep his equipment in plastic bags to reduce damage from the condensation that occurred when going from cold to warm areas. Despite the extreme contrasts between bright snow and dark objects, he said he avoids the additional weight of flash, filter and reflector (which he admits are excellent tools), and chooses to bracket exposures, taking a series of the same image at different camera settings.

Like the land and the animals he photographs, Murphy endures long periods of exertion followed by hours of still observation. His dedication rewards us with a rare and insightful perspective on the tenacious, yet tenuous nature of life.

- Tom Murphy.Â

- Thomas Berry on our shared future.

- “Silence and Solitude: Yellowstone’s Winter Wilderness” (public library) by Murphy, forward by Tim Cahill.

- “Your children’s Yellowstone will be radically different,” The New York Times.

- Â Yellowstone Science: special report on the ecological implications of climate change on the park’s ecosystem, published by the National Forest Service, 2015.

- Page 28: Scientist Michael Tercek and his daughter.Â

- “Natural beauty at risk: Preparing for change in western parks,” by NASA Earth Observatory blog.

Leave a Reply