When we contemplate Earth’s beauty, we tap into a source of strength that will last a lifetime, wrote Rachel Carson, a marine biologist and conservationist who became one of the finest nature writers of the 20th century.

Nature as balm for the soul is what children’s book author Eve Bunting writes of in her 1991 children’s picture book “Night Tree,” a story of a young boy and his family who make an annual visit to decorate an evergreen tree with food for forest animals on Christmas Eve. The sweet story touches on what humans have intuitively known and what science now illuminates: Nature is good for us.

We’re happier and healthier after a walk in the woods, according to a growing body of research that suggests regular interaction with wilderness is a buttress against today’s stressors.

“These experiences refresh our lives, teach us self-reliance, and reveal the wisdom of the cycles of the land,†said wildlife photographer Tom Murphy. “By contrast, the noises and distractions of our modern world induce loneliness and isolation.”

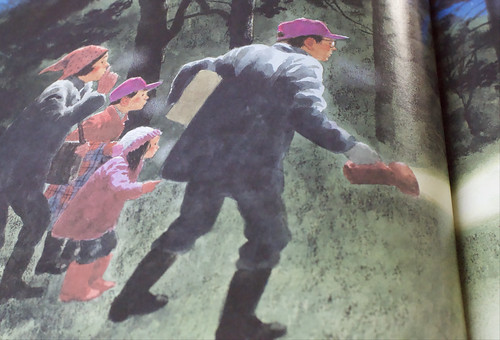

Like Murphy’s winter pilgrimages to Yellowstone National Park, Bunting’s family cherishes its contact with what is usually wild and hidden, as well as the effort needed to get there. With watercolor illustrations by Ted Rand, the story opens with the unnamed young narrator, his little sister, Nina, and his parents leaving their house where a Christmas tree is displayed in its front window. Bunting wrote:

“Dad sets our box in the back of the truck with the rest of his stuff and four of us squish into the front seat. We drive through the bright Christmas streets to where the dark and quiet begin. … Dad says it’s not really a forest, just a nice forgotten place where our town ends.”

As the family enters the dark, quiet forest, the boy notices the piney smell of the evergreens, the starkness of bare alder and maple, the many stars. It was cold enough that each breath hurt, so they hurried down the path.

Bunting wrote:

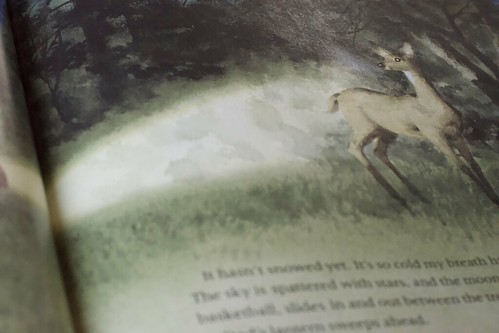

“Dad’s lantern sweeps ahead.

‘Look,’ he whispers.

We stop. A deer is watching us. I see the brightness of its eyes; then it turns and it’s gone.

An owl hoots, deep in the darkness. There are secrets all around us.”

The scruffy patch of forest manages to be at once familiar, yet wild, year after year. Helping a child develop an intimate, emotional connection to nature lays the foundation for later intellectual understanding and appreciation, according to Carson (1907-1964). In her 1965 book “A Sense of Wonder,” she wrote:

“I sincerely believe that for the child, and for the parent seeking to guide him, it is not half so important to know as to feel when introducing a young child to the natural world. If facts are the seeds that later produce knowledge and wisdom, then the emotions and the impressions of the senses are the fertile soil in which the seeds must grow. The years of early childhood are the time to prepare the soil.”

Bunting described how the boy is comforted by the family’s annual tradition, which provides a reassuring way to measure growth and change. She wrote:

“‘Here’s our tree,’ Dad says.

It has been our tree forever and ever. We walk around it, touching it.

‘It’s grown since last year,’ I say.

Mom puts her hand on my shoulder.

‘So have you.'”

When we encourage our children to seek solace in wild places, we give them a tool with healing capacity that extends beyond individual emotional and physical health to include the welfare of the Earth. How our children interact with nature, and how they raise their own children will determine the future conditions of our daily lives.

The boy enjoys making the balls of sunflower seed and millet, knowing the forest animals could use the food, and he savors the mystery of each visit to a forest cloaked in darkness.

Growing interest in the concept of forest bathing or shinrin-yoku, a traditional Japanese practice of immersing oneself in nature by mindfully using all the senses, is a result of mounting evidence that nature can positively influence our physical, emotional, and spiritual health.

Until recently, Western researchers largely ignored the concept of nature therapy such as shinrin-yoku, which has been widely studied in China and Japan where it is found to improve immunity and heart health, reduce allergies and other lung diseases, relieve depression and anxiety, and promote feelings of gratitude and selflessness, according to review published in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health.

While I appreciate the physiological and psychological benefits, they fade in import as I enter a forest. Like Bunting’s young narrator, year after year I went with my parents into the forest where the “dark and quiet begin,” something I continued with my own children.

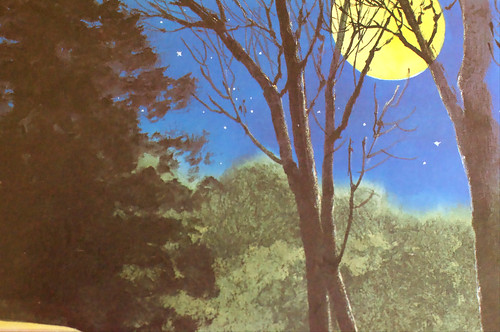

Within tradition lies mystery. There is always a hint of uncertainty, of danger, magic, and possible transformation when we enter a forest. I suggest this extends to even the corner tree lot where rows of trees encourage one to wander through them, brushing fingers against soft needles and breathing in the sweet woodsy perfume.

“Those who contemplate the beauty of the earth find reserves of strength that will endure as long as life lasts,†Carson wrote.

This year, my family’s journey ended at the corner lot a mile from home. While in line to pick up our tree, the car died. While some waited for a stranger’s jumpstart, the rest of us trekked home. It was cold, and my son and I hurried down the sidewalk as the moon slipped between apartment buildings in the growing dark.

- “A Sense of Wonder” (public library) by Rachel Carson.

- “Night Tree” (public library) by Eve Bunting, illustrated by Ted Rand.

- Wildlife photographer Tom Murphy.

- A scientific review of research into nature therapy and forest bathing.

- The forest in literature.

- My family tree: A new kind of carol, Unwrapping Christmas, Christmas, past and present, Behind the pageantry, Pocket tree.

Leave a Reply