At a restaurant table on Greenwood Avenue, I broke open a fortune cookie, pulled out the slip of paper, and read: Allow your curiosity to lead you to the answer you seek. I nibbled the cookie.

Curiosity is a hungry emotion. As my mind wanders deep into an unknown subject, it growls for attention, hankers for tidbits and factoids, yearns to fill the emptiness its questions create. Other times, short answers satiate its cravings, and curiosity is satisfied. For the moment.

Here is a short list of subjects where I am both ignorant and interested: Russian literature, homelessness, history, economics, croissant dough, black culture, geology, roller derby, bird calls, menopause, physics, tree identification, tax withholdings, flip-turns, ergonomics, and correct comma use.

Crumbs dropped on the restaurant table as I considered the subjects where I remain willfully, even happily, uninformed: trigonometry, tofu creation, pop culture, frisbee throwing, automotive repair, sushi assembly, coding. Then there were issues where I’ve the most rudimentary understanding: Korea, interest rates, Brexit, Chinese trade war.

Into my mind popped an interview with author Zadie Smith where she discusses her interest in self-imposed limits on knowledge. “An essential part of our power is this freedom not to think too deeply about the matter,” Smith said in an interview following the New Yorker’s 2013 publication of “The Embassy of Cambodia.” I scanned the short story and found where Smith, through the narrator, commented on the concept of imperfect knowledge. She wrote:

“… if we followed the history of every little country in this world–in its dramatic as well as quiet times–we would have no space left in which to live our own lives or to apply ourselves to our necessary tasks, never mind indulge in occasional pleasures … Surely there is something to be said for drawing a circle around our attention and remaining within that circle. But how large should this circle be?”

A breach of information, a blurring at the circle’s perimeter, is the geography of imperfect knowledge. Our circles should be large, expansive, inclusive, so that we feel vulnerable. To feel small and exposed, to be uncomfortable and worried–to know that we don’t know–might compel us to care more, work harder, and act with greater deliberation, knowing that life and action reverberated. This is how empathy is built.

Skeptical that empathy naturally occurs on a large scale, Smith argued for its legislation. I see her point. I’m not in the habit of making myself vulnerable and anxious for the greater good. My fingers folded and unfolded the fortune written on the paper slip: Allow your curiosity to lead you to the answer you seek.

Learning begins with curiosity. If it stops there, then it remains a collection of facts that stale and harden over time. Through observation and experience, facts become information and ideas. Connections made between ideas creates knowledge. Connections made between people builds empathy.

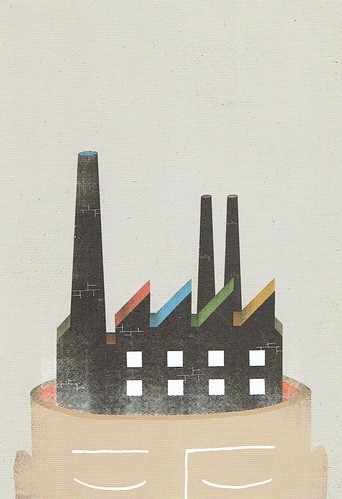

Noegenesis entered the lexicon in 1923 when the English psychologist Charles Spearman combined the Greek words noetic (I see or understand) with genesis (origin). It is defined as the production of knowledge. The concept of the mind as factory was advanced by the adman James Webb Young (1886-1973) in his streamlined, typo-troubled book, “A Technique for Producing Ideas.”

Young suggested that the mind’s method for producing ideas is as exacting as that used to produce an automobile.

“What is most valuable to know is not where to look for a particular idea, but how to train the mind in the method by which ideas are produced; and how to grasp the principles which are the source of all ideas,” he said.

Young identified two principles needed for the production of ideas:

- An idea is nothing more nor less than a new combination of old elements;

- The ability to bring old elements into new combinations depends on the ability to see relationships.

To capitalize on the principles, he suggested five steps:

Gather material, both specific and general. Young suggested writing the bits of information, experiences, etc. on three-by-five index cards, or keeping a file or scrapbook, which he said will keep the research orderly, reduce the urge to shirk, and prepare you to produce ideas.

Mentally digest. This is where the mind turns over facts, examining each one in different light, bringing random facts together to see how they fit. “What you are seeking now is the relationship, a synthesis where everything will come together in a neat combination, like a jig-saw puzzle,” Young said.

As you do this, Young predicted that tentative, partial ideas will come to you. Write these down. “These are foreshadowing of the real idea that is to come, and expressing these in words forwards the process,” he said. As you puzzle over the facts, you’ll tire; don’t give up. Press on, Young said, because the mind has a second wind.

Incubate and recharge. When you’ve exhausted yourself, turn the problem over to the unconscious mind, and do what stimulates you–music, theater, novels, whatever, he said.

“In the first stage you have gathered your food,” Young said. “In the second you have masticated it well. Now the digestive process is on. Let it alone–but stimulate the flow of gastric juices. Now, if you have really done your part in these three stages of the process you will almost surely experience the fourth. Out of nowhere the Idea will appear.”

Eureka! A new idea is born.

I licked my index finger, pressed it against the largest cookie crumb, and lifted it to my mouth. Hansel dropped crumbs on the forest floor as he and his sister, Gretel, wandered into the forest. He planned to follow them home, but birds ate them instead.

Ideas must be shared. Like Hansel and his crumbs, the reception to an idea might fall short of one’s hopes. But the final step–public response–is necessary, Young argued, in order for an idea to react, adapt, morph, and, hopefully, spread.

“Do not make the mistake of holding your idea close to your chest at this stage,” Young said. “Submit it to the criticism of the judicious. When you do, a surprising thing will happen. You will find that a good idea has, as it were, self-expanding qualities. It stimulates those who see it to add to it. Thus possibilities in it which you have overlooked will come to light.”

Alone, Hansel remained lost and trapped. Sharing the problem with his sister introduced possibility: They escaped the witch, crossed a lake, and found their way out of the forest. They made it home. I brushed the last cookie crumbs off my lap, paid the bill, and headed there myself.

- Zadie Smith and “The Embassy of Cambodia.”

- “A Technique for Producing Ideas” (public library) by James Webb Young.

- Noegenesis creator Charles Spearman and illustrator The Project Twins.

- “The Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm,” (public library) edited by Noel Daniel.

Leave a Reply