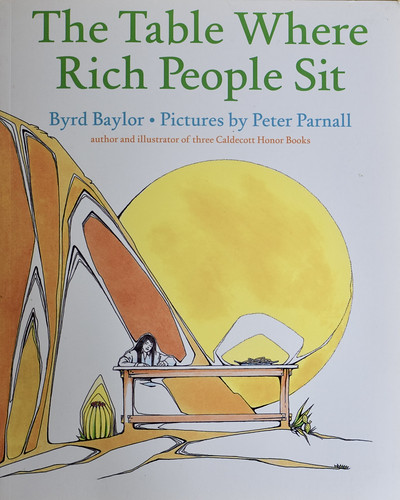

“Understand, I like this table fine. All I’m saying, is you can tell it didn’t come from a furniture store.” From Byrd Baylor’s “The Table Where Rich People Sit.”

The intimate and enduring exchange that can occur when people live close to the land is at the heart of Byrd Baylor’s picture book, “The Table Where Rich People Sit,” which explores the conflict of priorities between a young girl and her parents.

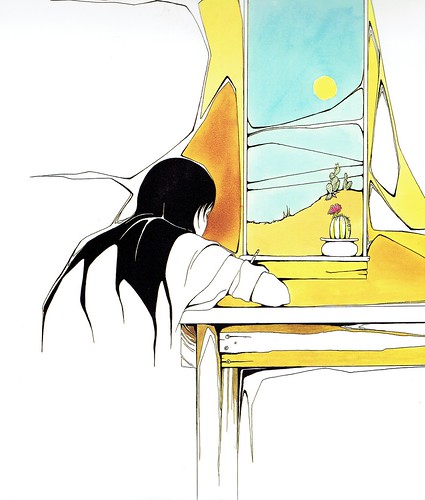

Written in 1994, Baylor’s rhythmic prose poem examines Mountain Girl’s bafflement toward her parents’ decision to live simply and lightly in a desert illustrated with pen-and-ink drawings by Peter Parnall. Four of Baylor’s books have been awarded the Caldecott Honor, runner-up to the year’s most distinguished American picture book for children.

“If you could see us

sitting here

at our old,

scratched-up kitchen table,

you’d know that we aren’t rich.But my father

is trying to tell us we are.Doesn’t he notice

my worn-out shoes?

Or that my little brother

has patches

on the pants he wears

to first grade? …‘You can’t fool me,’

I say. ‘We’re poor.

Would rich people sit

at a table like this?’ “

Mountain Girl challenges her parents’ decision to place their deep connection to and love for the land over a paycheck and stability. Her parents insist that they are rich.

“They used to tell us that

the truck just knew

which roads to take

and the coyotes showed them

where to look for gold–

but I never did believe it.After a month or two out there,

they always had a little bit of gold to sell,

but you can tell

it never made them rich.As far as I can see,

it was just an excuse

to camp

in some beautiful wild place

again.”

Mountain Girl’s parents hand their daughter a pencil and paper, agreeing to add up their money while she acts as bookkeeper. How much, they ask, is it worth to be able to work outdoors, surrounded by cliffs, canyons, desert, and mountains? How much is being able to sleep under the stars? What’s it worth, to listen to the coyote sing and see the cactus bloom? To pan for gold in a dry streambed?

“My mother says,

‘We don’t just

take our pay

in cash,

you know.

We have a special plan

so we get paid

in sunsets, too,

and in having time

to hike around the canyons

and look for eagle nests.’ “

This is a family who is far from wealthy, but neither is it experiencing real poverty. Instead, Baylor’s family has made an intentional choice to value what cannot be bought, a sentiment that echoed my own childhood. Like Mountain Girl, I grew up in “open country, alone, free as a lizard, not following trails, not having a plan, just turning whatever way the wind turns me.” Like Mountain Girl, I grew up wanting things that others obtained easily–Nike sneakers, 501 jeans, contact lenses. And like her, I was frustrated.

“I tell my parents

they should both get

better jobs

so we could buy

a lot of

nice new things.

I tell them

I look worse

than anyone

in school.‘I hate to bring this up,’ I say,

‘but it would help

if you both had a little more

ambition.’ “

This clash in priorities between Baylor’s parents and their child is played out on a grand scale in Ursula K. Le Guin’s novel, “The Dispossessed,” when she described the difference between people from neighboring planets–the first capitalist, the second anarchist.

“Here you see the jewels, there you see the eyes. And in the eyes you see the splendor, the splendor of the human spirit. Because our men and women are free–possessing nothing, they are free. And you the possessors are possessed. You are all in jail. Each alone, solitary, with a heap of what he owns.”

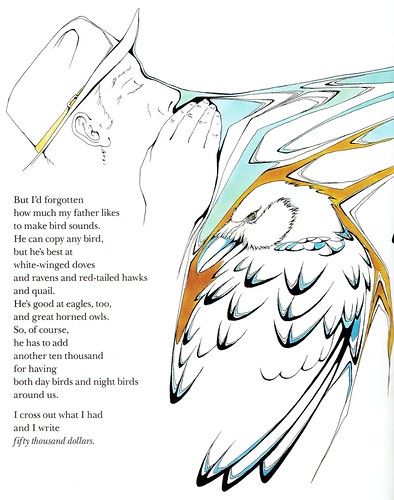

“I’d forgotten how much my father likes to make bird sounds. … So, of course, he has to add another ten thousand for having both day birds and night birds around us.”

From the “Table Where Rich People Sit” by Byrd Baylor; illustrated by Peter Parnall, 1994.

It’s a conflict that continues within my own relationship with my parents as they age. Frugality, family, self-reliance, and land stewardship–values that sustained a young family in Nevada’s high desert–now equate to less cash and fewer options in retirement.

During a recent visit, I worried, fretted, schemed, and cajoled them to make a plan, to prepare for when poor health prevented them from caring for the land and each other, to anticipate the end.

Choose one of your six children, I pleaded, so that we can make room for you in our homes and in our lives, once again.

Instead, my mother talked of planting a field of flowers for her honey bees; my father laid irrigation line. Acts of love–for life, and for me, their daughter. After they left, I wondered at my own advice and their reticence to take it. Had I overlooked something? Was it a failure to value the land, to recognize their deep reverence for the home built and the life lived there?

“(My mother) says she can tell time by the way colors (of mountain shadow) change from dawn to dark.”

As Mountain Girl’s parents put a price tag on their decision to value place over paycheck, she begins to catch on:

“To tell the truth,

the cash part

doesn’t seem to matter

anymore.I suggest

it shouldn’t even be

on a list

of our kind of riches.”

Author and naturalist Terry Tempest Williams said that for years she wandered the desert, seeking a narrative in a place that eluded her.

“But when I stopped searching and settled into the erosional peace of the redrock desert, I found myself quietly held by an immensity I could not name,” Williams wrote in “When Women Were Birds: Fifty-Four Variations on Voice.” “I took off my clothes and lay on my back in a dry arroyo and allowed the heat absorbed in the pink sand to enter every cell in my body. I closed my eyes and simply became another breathing presence on the planet.”

Communion–be it a shared loaf or time spent on beloved land–brings nourishment, peace, and absolution.

Perhaps my parents, like those in Baylor’s book, were surprised by their daughter’s questions, maybe they were uncertain how to explain that connection to land can rival that to family.

Home.

Land.

At the end of their visit, my parents returned from whence they came, to a shabby and tired trailer, sagging and spent, like the bodies we all will one day inhabit. The tremendous energy it takes to care for their home will continue to be repaid in nights of shimmering starlight, in winds scented with petrichor and sage, and in the flicker of memories that grow stronger as life recedes.

- The Table Where Rich People Sit (public library.)

- Byrd Baylor, The Arizona Republic, 2009.

- Peter Parnall.

- Ursula K. Le Guin, mentor.

- Terry Tempest Williams’ meditation on women’s voices is a prayer of bird song, blank page.

- Petrichor, defined through life experience.

Leave a Reply