Stories keep us alive, screenwriter and graphic novelist Brian McDonald said. He stood before a roomful of writers, all of us there to figure out how to tell a story, something that should’ve come instinctually if it was, as claimed, as basic as food and sex.

“They contain the wisdom we need to survive,” McDonald said during the talk and (with less interruption and more succinctness) on his website. “They’re essential for us as we live in and navigate the world around us. They are our hope when we are in despair. They are our guide when we’ve lost our way. And they are our inspiration when we are weary.”

But let’s back up a minute, he insisted, and first agree on what is a story. Stumped by its structure, the room made even less headway on story’s definition. It’s entertainment, someone called from the back of the room. It’s a narrative, came a suggestion from one side. It’s a beginning, middle and end. Yes, yes, McDonald said, it’s all that and more.

A story, he said, is the telling of events that come to a conclusion. The difference between it and a child rambling on about her day ... and then I went outside and I kicked a ball and it went over the neighbor’s fence, and then I went inside and ate lunch, and then … is that a story has a point, he said.

Despite the proliferation of and need for stories, they don’t come easy. At least, not for me. One way to ensure originality and meaning is to use a story spine, McDonald said, a method that reduces a story to its essentials.

A story spine is fill-in-the-blank exercise: Once upon a time _____. And everyday _____. Until one day _____. And because of this_____. And because of this _____. Until finally _____. And ever since that day _____.

Story spine was in the back of my mind when I started reading Lynda Barry’s new book, “Making Comics.” For a number of years she’s been drawing and writing her way to understanding the interconnection between image and story.

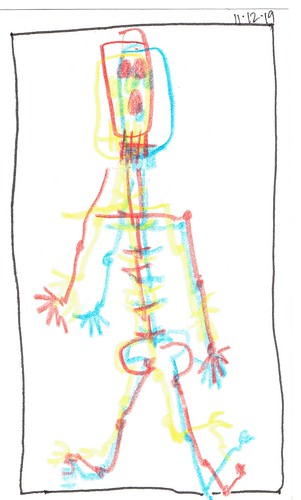

“Line and shape reveal the image world, the ‘Once upon a time’ of now,” Barry wrote. “Kids speak image. They are fluent in a way that allows me new understanding about a certain state of mind that twins itself with certain activities. It’s something I can’t learn by talking about theory or by talking in general. This is a different sort of language. … This language moves up through your hand and into your head.”

Whether the ideas of Barry and McDonald make their way into my writing becomes less important as I puzzle out how to fit a story into a spine, draw with my eyes closed, draw for three minutes, draw for no reason at all. Maybe, the point is the process as I feel my mind loosen up, become supple and playful. Backfilling spines and blind-drawing a couple of the story examples McDonald gave us in the class has just been plain old fun.

My first spine is based on a 60-Minutes news story:

Once upon a time there was a man who lived by the sea. And everyday the man fished for his dinner and shared his catch with the sea. Until one day, the man ate all the fish he caught and the sea went hungry. And because of this the sea went to search for food elsewhere, pulling away from the shore. But still the man ignored the sea. And because of this the sea grew angry and remembered it hadn’t tasted man in a long time, so shaped itself into a giant wave. Until finally, the sea rushed forward and swallowed the man. And ever since, the man’s descendants are watchful of the sea’s appetite so that they might flee to higher ground when it, once again, grows hungry for man.

The second story is inspired by an Inuit tale:

Once upon a time the northern lights watched children playing in a dark, frozen land. And every day the northern lights watched the children, bundled head to toe in snowsuits, hats, mittens and boots, chase and dance and skip and leap in the snow. And every night the northern lights practiced playing as it chased, danced, skipped and leaped across the black sky. Until one day the children brought out a ball and kicked and tossed it back and forth. The northern lights had no ball and so couldn’t play. And because of this the northern lights began its search: The first ball it found was a boulder, but it was too heavy and dropped out of the sky. They second was a hibernating bear that woke, grumpily, and waddled off in need of more sleep. Until finally, the northern lights spotted the round head of a child who’d left the house without her hat. Ever so lightly, it sneaked up on the child and plucked off her head. And ever since, the child’s head has been used in a sky-sized game of kickball, and children know to wear their hats when they go outside.

- Brian McDonald, screenwriter and graphic artist.

- Lynda Barry, cartoonist, teacher, blank Scrabble square.

- “Making Comics” (public library).

- 60 Minutes story “Sea Gypsies Saw Signs in the Waves.”

- National Public Radio report “Storytelling instead of scolding.”Â

Leave a Reply