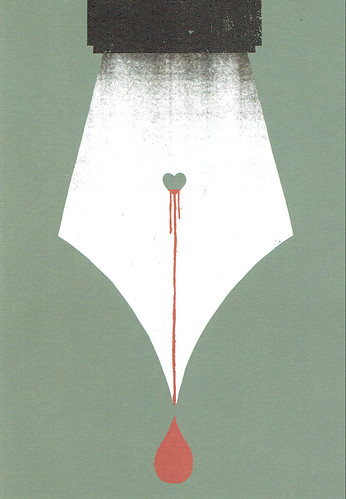

Sometimes only the scripturient desire to scratch frustration and fear into paper, to grip the pen and press its tip until it bleeds, to watch the ink pool and smear, to rip paper as I write, allows my mind to finally let go of the emotions.

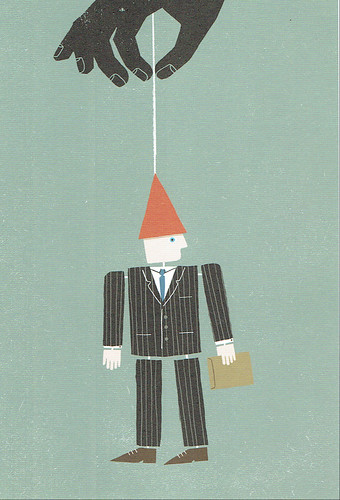

Those who live with me regularly find me in a foment of irritation, agitation, and consternation over some inept act or declaration uttered by the quockerwodger leading the nation. The media’s daily mastication of the ultracrepidarian’s addled tweets creates a fermentative sludge of sour thought in minds gorged on news.

I try not to stew in the thoughts. I know that physical activity eases the mind because I buried 200 daffodils as anger management. I slogged through ankle-deep slush to make a physical therapy appointment for the chronic pain in my neck. I dragged my husband to zydeco lessons, am learning the angry art of roller derby, and am taking yet one more yoga class.

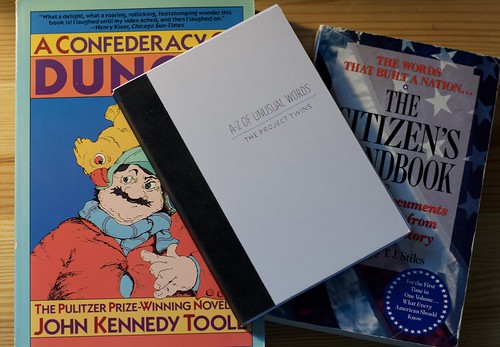

Here in this state of fret and fuss–returning to The New York Times, returning to Twitter, returning to read and re-read the same discouraging news–I picked up a small, modest book called “A-Z of Unusual Words,” tucked in between “A Confederacy of Dunces” and “The Citizen’s Handbook: Essential Documents and Speeches from American History” on my bookshelf.

The book is a set of bound postcards illustrating 26 rare words created in 2011 by twin brothers and design partners James and Michael Fitzgerald, an Irish based graphic art team. In the eight years I have owned it, I occasionally would take it off the shelf to thumb through the pages, studying the delicate line and restrained color of the illustrations before flipping them over to read the short definitions on the back.

This time many of the postcards seemed relevant to right now: Unusual words for an unusual state of mind and time. So an exercise was formed to manage the moment, to use an obscure alphabet to untangle a welter of ordinary emotion. What you now read was an effort to lessen fear, impotence, denial, and outrage over the state of all things.

No single issue feels as foreign nor as frightening as climate change, which envelopes all other struggles–immigration, race, wealth, foreign policy, justice, and inequality–within its larger threat. We are in a state of zugzwang, a position in the game of chess where any move will bring serious and decisive disadvantage.

Humans are permanently changing the world’s geology, chemistry, and biology. Our refusal to align our own functions with the ecological processes on which we depend threatens our future, said pioneering eco-theologian Thomas Berry (1914-2009).

Berry warned in “Evening Thoughts: Reflecting on the Earth as Sacred Community†(2006), that the twin paths of industry and technology, which have led us to pinnacles of achievement, are also roads to destruction through exploitation of shared resources. To avoid ecological disaster, Berry said we must redefine progress: Our well-being must realign with that of the Earth’s–a challenge of such immensity it threatens to gorgonize me into inaction.

“To question progress is to commit the ultimate absurdity, paralyze human activity, destroy basic values, and take away existing security,” Â Berry wrote.

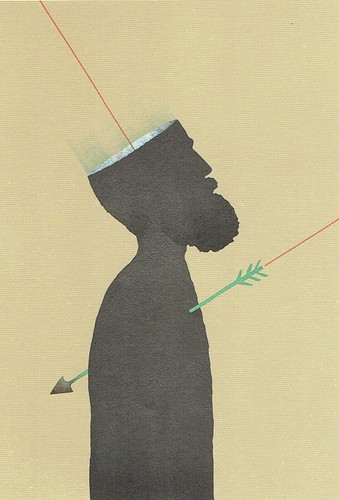

Will hubris be the character flaw that we fail to recognize and overcome? Will excessive pride that elevates human need and desire above all other living forms be Aristotle’s hamartia, the arrow that misses its mark, the error that ends in the hero’s tragedy?

“We cannot survive if the conditions of life itself are not protected,” Berry wrote. “We cannot make a blade of grass, but there is liable not to be a blade of grass unless we accept it, protect it, and foster it.”

Berry’s apocalyptic language is a harbinger of David Wallace-Wells, who argued in The New York Times’ opinion pages that now was the time for climate panic. The verbal pummeling is not a recumbentibus, but rather a call to action. Fear, Wallace-Wells said, could save us.

Which means I’m not down for the count, despite appearances. The secret to getting up is found in one final word of this obscure alphabet.

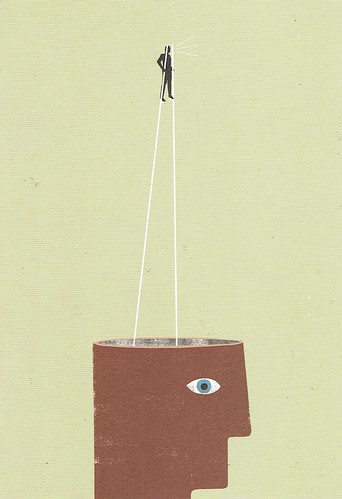

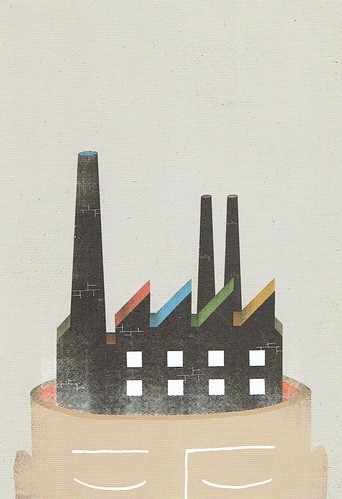

Noegenesis, coined in 1923 by an English psychologist who combined the Greek words noetic (I see or understand) with genesis (origin), is defined as the production of knowledge. New thoughts are formed through three steps: observation, experience, and in finding connections between ideas. Learning to leverage the severity of the threat, depth of fear, and degree of impotence in order to overcome what frustrates and fills me with anxiety is a worthy goal.

The novelty of learning new words is more than a diversion. It is sustenance for a weary mind. And to find that an image of the mind as factory can serve as inspiration is an irony as delicious as the fortifying thought that we can learn our way to a solution.

- The Project Twins.

- Thomas Berry.

- “Time to Panic” by David Wallace-Wells, The New York Times.

Leave a Reply