Bird song and blank page are interwoven into a beautiful meditation on women’s voices and women’s silence in writer and naturalist Terry Tempest William’s book “When Women Were Birds.” Bequeathed her mother’s empty journals, Williams struggled to explain their inviolable silence: My Mother’s Journals are paper tombstones.

This beginning was followed by a blank page. Then another. With nothing to read, my eyes watched my fingers as they picked up the corner of a page and separated it from those beneath. I studied my hand as it slid across the white surface and I listened to the quiet, rhythmic hush it created. Mind quieted. Shush. Shush. I turned the fifth page to find words, once more.

“What is voice?” Williams asked. “My mother’s voice is a lullaby in my cells. When I am still, my body feels her breathing.”

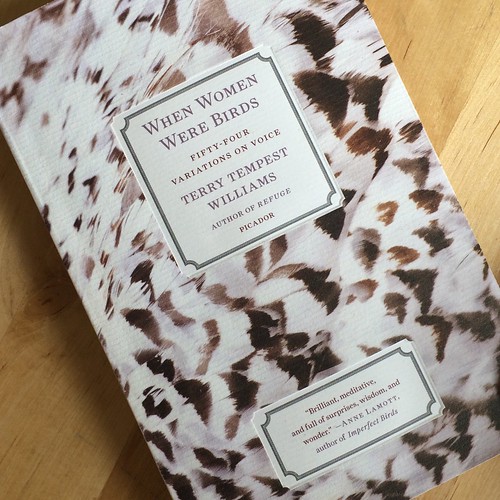

Published in 2012, “When Women Were Birds: Fifty-four Variations on Voice” grows in relevancy as our nation convulses over issues of abortion and climate change. It is a prayer on how to live as women, a lyrical essay to mother, daughter, and grandmother, to all whose sacrifice and silence became a citadel and whose voices sang out against the pain and injustice leveled against their bodies and the Earth.

“I am fifty-four years old, the age my mother was when she died,” Williams said. “The questions I hold now could not have been comprehended when I was a woman in my twenties. I didn’t realize how young she was, but isn’t that the conceit of mothers–that we conceal our youth and exist only for our children? … What my mother wanted to do and what she was able to do remain her secret. We all have our secrets. I hold mine. To withhold words is power. But to share our words with others, openly and honestly, is also power.”

Williams’ recognition of the concurrent strengths of voice and silence is shared by sculptor Anne Truitt (1921-2004), who wrote, “I am as honest as I can be about what I write–that is a moral imperative–but I ‘retain my reticences’: I omit, abbreviate, abridge and retrench. The keep of my castle remains private.”

Williams goes on to explore through a kaleidoscope of overlapping lenses–motherhood, her Mormon faith, the environmental movement, her family’s multigenerational struggle with cancer–the inherent threat that exists when silence dominates and becomes what she calls a personal crucifix.

“My mother’s transgression was hunger,” Williams said. “She passed her hunger on to me without ever speaking a word. Solitude is a memory of water. I live in the desert. And every day I am thirsty.

“When I opened my mother’s journals and read emptiness, it translated to longing, the same hunger and thirst Mother translated to me. I will rewrite this story, create my own story on the pages of my mothers’ journals.”

This unquenchable thirst for connection with each other and the Earth that Williams speaks is readily found in suffering and pain, a sentiment shared by playwright Young Jean Lee when she proffers that the “older you get, the more necessary it becomes to develop this public face that you put on to hide your pain,” and when author Ursula K. Le Guin writes, “We are brothers in what we share. In pain, which each of us must suffer alone, in hunger, in poverty, in hope, we know our brotherhood.â€

Williams goes on to explain how she spent years searching for a narrative, a place where she belonged, for space to exist, for connection and understanding. In a short chapter that mirrors the environmental writer Roger Deakin’s ode to the pencil, Williams contemplates writing with a pencil in her mother’s blank journals.

“I like the idea of erasure. The permanence of ink is an illusion,” Williams said. “Ink fades and is absorbed into the paper. Water can smear it. Ink runs out. A pencil can be sharpened repeatedly and then disappear in the process. Like me. …

“Erasure. What every woman knows but rarely discusses. I don’t mind erasure if it is done by my own hand. My choice. Write a word. Not the right word. Turn the pencil upside down, erase. Back and forth on the page. Pencil upright. Begin again. Point on the page. Pause. Find the right word. Write the word. Word by word, the language of women so often begins with a whisper. …

“When silence is a choice, it is an unnerving presence. When silence is imposed, it is censorship.”

The mother’s journals remained empty. The daughter will never learn why. In her search for understanding, Williams’ answers became a collection, a mantra, a poem, a prayer: My Mother’s Journals are a paper cut. My Mother’s Journals are salt. My Mother’s Journals are a projection screen. My Mother’s journals are white flags of surrender. My Mother’s Journals are a cruelty. My Mother’s Journals are a myth.

What began as a book about voice, a call to her sisters to speak the truth of their lives, ended with Williams’ admittance to the failure of words and an acknowledgment of silence’s sacred power.

“It is not in sorrow that I am moved to speak or act, but in the beauty of what remains. … I want to speak and comprehend words of wounding without having those words become the landscape where I dwell. I want to possess a light touch that can elevate darkness to the realm of stars.”

Like the ecotheologian Thomas Berry, Williams turns, in the end, to myth in order to speak of the beauty and pain of her world and ours.

“Once upon a time, when women were birds, there was the simple understanding that to sing at dawn and to sing at dusk was to heal the world through joy,” Williams wrote. “My voice rises again and again in beauty within the wonder and awe of the spectacle: an exaltation of larks; the murmuration of starlings; a murder of crows; a parliament of owls. … The birds still remember what we have forgotten, that the world is meant to be celebrated.”

- Soupçon or sounds of collecting.

- Terry Tempest Williams’ “When Women Were Birds” (public library).

- Anne Truitt on pathways between connection and privacy.

- Ursula K. Le Guin on why suffering unites us.

- We might be miserable, but Young Jean Lee doesn’t want us to be alone.

- Roger Deakin on the pencil’s tentative nature.

- Thomas Berry on the urgency of evolutionary epic.

Leave a Reply